|

September 2016 issue

|

|

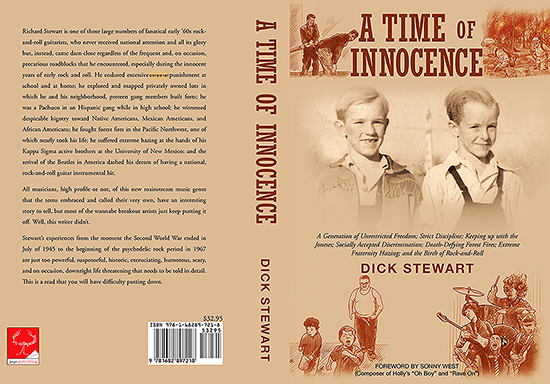

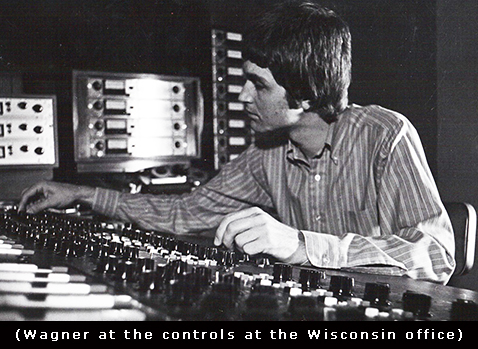

LEADING SOUND ENGINEER, JOHN WAGNER

He Came from Petty’s Studio (Interview conducted by Dick Stewart) |

Albuquerque, known officially as the Duke City and recently referred to as Burque (‘50s Hispanic slang), experienced its first garage band explosion in the early ‘60s during the instrumental craze, and it was inspired by the Ventures’ 1960’s instrumental guitar release of “Walk Don’t Run.” The band’s choice of guitar was the Fender, and the heavy use of the tremolo bar (whammy bar), tremolo, echo, and minor chords were infectious, and the result was the emergence in mass throughout the United States of instrumental guitar rock-and-roll combos (as they were called then). Fender guitars flew off the shelves and the cumbersome upright bass took a back seat. The Fender’s Precision electric bass replaced it because they were much easier to tote to the various venues, and the unique tones of the Fender Stratocasters, Jazzmasters, and Jaguars took center stage.

The first Albuquerque Ventures cover band of note was the Chessman; the second, the Knights, and the group’s unique instrumental-guitar/classical-piano rock release, “Precision” on Red Feather Records was a hit on KQEO AM radio in 1964, and it inspired a number of newly formed Albuquerque (mostly) vocal bands to head to the nearest sound studio to record and release their own 45s citing, “If the Knights can do it, we can too,” but with whom?

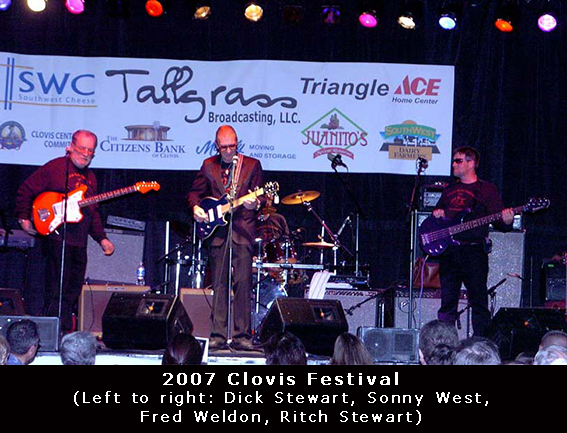

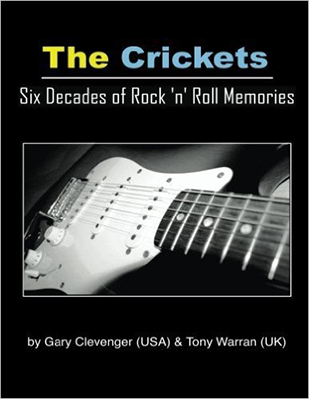

In Albuquerque in the early to mid-‘60s, there was Red Feather Records on San Mateo Blvd near UNM, and in Clovis, New Mexico, about 219 miles east of Albuquerque, there was legendary sound man named Norman Petty, who was responsible for the production of a number of hits, the most notable by Buddy Holly and the Crickets: “That’ll Be the Day,” “Oh Boy,” and “Rave On.”

Then along came John Wagner from Clovis to the Duke City in 1964 because his dream of being Petty’s apprentice was unceremoniously dashed by the man himself. Another reason was to attend the University of New Mexico where he earned an Electrical Engineering Degree.

John’s childhood years were spent living in rural areas near Clovis and shortly thereafter in a home community about ten miles south of Clovis that his dad built called Green Acres. When he entered fifth grade, his family moved to town, and he remain there throughout his high school years:

“My Dad had many jobs,” says John. “Public Utility in Portales, farmer, carpenter, plumber, home builder and anything he could find. My mom was a housewife and mother who assisted him in any way she could, [such as] house painting, [and] making clothes, etc."

During John’s preteen days, he and his compadres rode their bicycles, made dugouts, and built hideaways because electronic entertainment with the exception of a radio and a new-on-the-market black-and-white, rabbit-eared television with two broadcasting channels, didn’t exist.According to John, the physical environment on the outskirts of Clovis, in which he and his compadres explored, was a bit precarious and wreaked from a mix of oil, cow flops, and horse manure:

“There was a lake near my house south of Clovis,” says John, “where the Santa Fe Railroad dumped all the oil from the train locomotives that they needed to get rid of. We were told to stay away from it, but we tried to build a raft and float it across the lake. [It was] very dangerous, and things don't float so well in water mixed with oil. I hated insects, snakes and the like. I did try to play doctor once and do surgery on a turtle [and it was] not something I ever wanted to do again. It was a typical windblown Clovis terrain and a lot of tumbleweeds and dirt and lots of horses and cattle where I lived south of Clovis. I hated the rooster and chickens we had and never wanted to be a farmer. My brother had a boat and a little cabin at Ft. Sumner Lake and we went skiing there. I never liked fishing and still don't. I began to get interested in music about the time we moved to town.”

John loved his parents and said they were not into corporal punishment, which was common during those times. According to him, he was given a lot of freedom as long as he didn't do anything stupid:

“I was not too wild of a kid,” says John. “My Dad never laid a hand on me and my Mom gave me a few harmless swats on the behind. I tried to be sane, and if I did anything foolish any repercussion straightened me out quickly. I played Little League baseball and my Dad came to every game. I had a little powered midget race car my brother Dugar build for me and in a good part of middle school, I drove it all over Clovis just like a car.”

According to John, he never smoked, drank alcohol or got into serious trouble. Music, however, became his passion in his early teenage years, although his Dad was concerned about him and his band performing at the Midway in Clovis, as he considered them much too rough and rowdy. Nevertheless, Mr. Wagner was very proud of his son and came to a lot of his YRB dances.

“My dad was my greatest fan,” says John, “but he died when I started college, and I never really got to know him like I wished. I was [my parents’] last child and almost grew up like an only child because my brothers were all [so] much older.”

John did have a special bond with his brother, Dugar, who ran a car dealership and mechanic shop until John left for high school. He considered Dugar a second dad because his real Dad’s advanced age and old-fashioned ideas made communication with him more difficult. In addition, Dugar kept John’s car mechanically sound, and besides the midget race care, he built Wagner a trailer for his newly formed band called the Five Counts. John’s other brothers attended dental school, and together they opened a dentist office on Wyoming NE near Route 66 in Albuquerque, New Mexico in the late ‘50s.

According to John, Mickey, who is seven years older than him, is the closest to his age:

“He just didn't like me to be around his age group too much,” says John. “I do remember he was manager and projectionist at a drive-In-movie theatre and in-door theatres in town. I would get to go there and watch movies while he worked at times.”

John’s mother worked at the Mesa Theatre in Clovis, and after school, he would drop by and watch “Rocket Man” and Superman serials. When the Mesa shut down, Norman Petty bought it and turned it into a performance hall recording studio.

John became interested in playing the guitar shortly after Dugar had a motorcycle accident. To the best of his recollection, John was in the first grade. He remembers buying a five-minute guaranteed guitar course and practiced like mad until his fingers got so sore he had to quit. Dugar said he needed a much better guitar and they found a Kay f-hole arched top in the paper for $50:

“He went with me to get it, and I became more serious at that point. I listened to records and hung out at a service station near my house whose customer was Charlie Phillips, who wrote the hit ‘Sugar Time.’ Charlie asked me to come to a downtown street park [that was] being sponsored by ‘Pop’ Otis Echols, to play one song.”

John played a three-minute guitar boogie shuffle and became possessed with playing the guitar from then on:

“I started hanging with friends that were more accomplished on guitar and really wanted to get better,” says John. “I would go to the rock concerts at the Clovis Marshall Auditorium and see the likes of Cash, Orbison, Johnny Horton, Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, the Big Bopper and others. I knew that was what I wanted to do.

“I heard Bill Haley, Carl Perkins, Sonny Curtis and others at the time rock was forming. I was most taken in with Ray Charles, Jerry Lee and Little Richard. But Orbison and the Teen Kings were the magic moment. I then began hearing Buddy Holly on the radio and was in awe that he had recorded at Norman Petty's. My Brother Dugar was a mechanic for Norman's father, and I was aware of his studio. ‘Rock around the Clock’ was one of the first rock songs I remember. I like country artists like Sonny James and I was dying to learn ‘A White Sport Coat’ [by Marty Robins]." I really was enthralled by the sound of Ritchie Valens. [Chuck Berry’s] Johhny B Goode was always a favorite because I thought of it as scripture, and, of course, Elvis was an instant winner for me!”

According to John, Clovis was a segregated town, and although he witnessed it from time to time, it never became a problem for him:

“There was a school in the Black district called Lincoln Jackson. There might have been one or two Blacks in the public schools, and back then I really didn't understand the race situation too much. In the summertime I remember going to basketball camps at Lincoln Jackson and having a good time with no problems. I asked a black vocal group to get on stage at the YRB during one of the dances we played, and I remember they had to be allowed in, sing and then leave. I didn't really understand racial issues until leaving high school for college in Albuquerque. I did have quite a few fistfights and rough times in Clovis, but it was all caused by red-neck-bullying white farm boys.”

Because of the guitar-instrumental rock-and-roll explosion, which was inspired by Norman Petty’s late ‘50s instrumental releases of Raton, New Mexico’s Fireballs and West Texas’ String-A-Longs and later brought to a higher level of performances by Southern California’s Dwaine Eddy and Washington State’s Ventures, John went in the direction of an instrumental-rock guitarist and headed for the Norman Petty Studio in the early ‘60s to begin laying down some tracks:

“I loved the Ventures’ ‘Walk Don't Run’ and really got excited about instrumentals when ‘Torque’ by the Fireballs and ‘Wheels’ by the String-A-Longs [came out]. Dwaine Eddy was a big influence. When we recorded at Norman's in about 1960 we did ‘Leave My Woman Alone’ by Ray Charles with James Usery singing and several instrumentals that I wrote. Ace records released a package of instrumentals from the ‘60s titled by one of my songs, ‘That's Swift!’ Another one of my instrumentals on that release is ‘Skuzzy.’

“When I started to get serious about guitar, I listened to Barney Kessel and other great jazz guitarists. But Chuck Berry was my hero and many others kept coming. [Editor’s note: Most of the budding rock-and-roll guitarists of the time worshipped Berry, and many of them considered him the god father of rock and roll.]

“I liked country then, but didn't really do much country music as a performer or producer until my mid ‘20s and early ‘30s. I loved Chet Atkins and bought his records, but I didn't think I could ever do his Travis style of finger picking [Editor’s note: playing rhythm and lead at the same time with the same hand]. I [stayed] with simple styles [that] I could learn on my own.”

“Buddy Holly was one of my favorites. I would hear ‘That'll Be the Day’ and ‘Peggy Sue’ on the radio and was so excited it was recorded in my home town. Clovis was a great place to be in the ‘50s and ‘60s music era. I felt like I was in the center of the musical universe.”

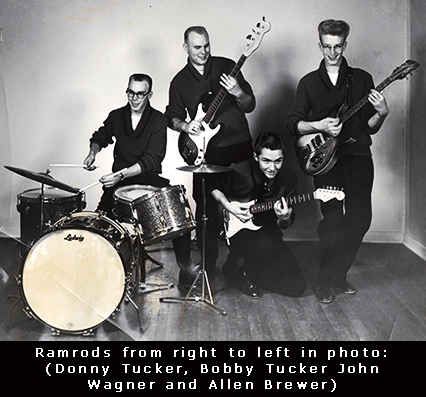

John’s first band, which he considered a real band, was called the Ramrods and he formed it during his early high school years at Clovis High. His band members were Alan Brewer, Donny Tucker and his brother, Bob, and the boys’ specialty was instrumental guitar performances, covering tunes by the Ventures, Champs and Fireballs. After being together for a few years, the group recorded a single in the garage of the Tucker brothers’ father. A 45 rpm record was made, and John gave it to his choral high school teacher, who gave it to Petty as what john refers to as a sort of introduction.

When John wasn’t rehearsing, he spent a lot of time dragging main street with his 52 Plymouth two-door coup that had April Paris Rose and Smooth Operator painted on it, and because all the teens with wheels drove up and down main street, too, it was a certainty that he would run into others who didn’t take kindly to the coup’s look. The result was a few ugly fights with the local farm boys, as john called them. [Editor’s note: They were called stompers in Albuquerque during the ‘50s and ‘60s, and many wore the Future Farmers of America jackets.]:

“I didn't date a lot in high school and focused a great deal on the band and getting jobs. In about mid High School I formed a band named the 5 Counts and the members were Eddie Boling, Doug Roberts, James Usery, Phil Elliott and me. We became quite popular all over Eastern New Mexico and played Portales, Roswell, Hobbs, Artesia, Carlsbad and Clovis to name a few. We played my high school prom sharing the night with the Champs featuring Glen Campbell.

“I also worked as a cashier at a grocery store, but had to quit because my boss didn't like me playing music in a rock and roll band. I asked to get off an hour early one evening and he said I needed to make a choice. So I quit after two years of being a faithful employee. Most of [the male teens during that time] dressed and behaved like Elvis Presley with ducktail haircuts and the like. Pink and black were cool were cool, but I did not have taps on my shoes. My whole band had flat tops and hair combed back on the sides almost [in] a ducktail style. Doug Roberts went on to play with the Fireballs when I left for college. Phil Elliot did continue to play with Bluegrass bands in Texas and do well.

”John Wagner’s first session at Norman Petty’s studio was around 1960. He and his band, the 5 Counts, cut two vocals and three instrumentals with Petty as engineer and producer. The vocals were a Ray Charles song, “Leave My Woman Alone” and a Roy Orbison balled called “Trying to Get to You.” The guitar instrumentals were “Albuquerque” that sounded similar to the String-A-Longs’ hit, “Wheels,” “That’s Swift,” and “Skuzzy.” According to John, Norman told the band that he placed “Albuquerque” with a European label but the boys never saw a 45 rpm:

“My mom and I thought we were going to be stars,” says John, “but my dad reminded us not to get too excited about it. As usual my dad was right.”

Norman told the band members that it would be a while to get a release, which John hoped to mean he wanted to encourage the 5 Counts not to get discouraged and continue creating music. Wagner, however, did get the feeling that it would be hard to get Petty to do more sessions with the band unless something positive took place, adding that Norman had a strange personality, but was very nice to him and the boys on their first recordings:

“[When] my high school chorus teacher gave Norman a garage recording we did, he offered to sign us when I met him and talked with him. He said he would publish the songs we wrote and record us on speculation. I know he was known for putting his name on things that he altered or made a change to, but I have never seen our copyrights and would not know if he did that to us. I heard complaints about that from other people but have no direct experience I can present.”

John was impressed with Petty’s engineering genius and marveled over his ability to capture that right sound and appealing hook, which resulted in releases that garnered national fame:

“Norman was nice to us when we worked there and I was in awe of the studio and the activity attached to Norman. I remember a cool and pleasant air conditioned studio. We recorded on mono Ampex machines and bounced between machines to overdub any additional tracks and vocals. His great achievement was the natural reverb echo chamber built in what was his father's car repair shop. I believe my brother worked there when it was built. I think we did use a box for drums on one song. We did several takes on each song until it seemed to be the best we could do.”

One day John talked to him about a possible apprentice and he welcomed the idea:

“We had done a couple of sessions, and I left for college in Albuquerque. My Clovis High girlfriend had broken it off with me when I left for school at UNM. During my first year of college she came to Albuquerque and looked me up and wanted to get married. I said okay and we planned to get married in the summer after my first year of engineering.

“I thought it would be great to study recording with Norman that summer and on a visit to Clovis, met Norman at the new theatre recording studio for a tour and asked him to let me intern in the upcoming summer. He said, ‘Sure, that would be fine.’ I got all excited and told my family and fiancé about it; I was really pumped.”

As summer neared, John brought up the intern concept again in a phone conversation, but Petty’s demeanor had changed. According to John, Norman told him flippantly that he couldn’t remember the conversation about a possible apprenticeship and had no interest in the idea, anyway. Wagner was crushed and embarrassed; but it didn’t kill his dream. It stimulated it:

“I decided I would just start a studio in Albuquerque and learn on my own. [It was] an act of rebellion. I had always planned to go to UNM and study electrical engineering [anyway, but I hadn’t planned on starting a studio until Petty’s caustic reply]. I had some equipment and [had experimented with it] as a hobby, but [it was] mostly for playing jobs. [During my] second year of college I built a studio in my brother's dental office. There was a concrete hallway in the front of the dental office, and I painted it with glossy paint and put a speaker and mike in it to send a signal through [for an echo effect]. Eventually I got a Fairchild Hammond spring reverb as an upgrade.

“I spent every moment there and started producing bands. Sidro and the Sneakers was one of the first rock bands. I signed Larry Brummet, Jerry DJ, and others. Lindy Blaskey recorded there, too. [Editor’s note: The Knights was John’s second band due to the success of “Precision” in 1964 on Red Feather Records. Three 45s were released on Delta.]

“I do believe that Norman rejecting my internship was a great gift to motivate me to the life I found [that was] much [more] valuable than a summer of hanging around his studio in Clovis. He handed me a lemon and I made lemonade.

“I went to Audio Industries Corp. on La Brea Ave. in L.A., asking about recording equipment. When they asked where I was from, I said Albuquerque, and they said their owner would be interested in that and would like to talk to me. He was very gracious and said he had equipped and worked with Norman to refine the 7th Street Studio. He had made trips to Clovis in his private airplane and knew Norman well. He gave many pointers and said I should, one piece at a time, buy professional gear and not waste money. He sold me two Altec duplex speakers and cabinets and a McIntosh 275 watt tube amp to power them. He would always talk to me, never forced sales on me, and gave me constant guidance.

“I got the feeling with time that he and Norman had parted ways, and I believe it had to do with Norman not liking him serving other clients in the Southwest. I really don't know, but as I grew, he was proud that I had started with nothing and became an actual competitor to Norman. Hal would always listen to my recordings and recommend ways to improve on my budget.

“I did ‘Not Just Jazz’ with Clyde Hankins and Arlen Asher as the first album I ever produced. That was the beginning.”

According to “Eleven Unsung Heroes of Early Rock and Roll,” Hankins, who sadly passed away in 2006 at the age of 88, was an Albuquerque Jazz-guitar legend who sold a number of relatively new-on-the-market Fender Stratocaster guitars (he was the first recipient of the Strat in Texas and not Holly as many believe) to a growing number of aspiring rock-and-roll artists in Lubbock, Texas while he was employed at Adair in the late ‘50s, including Buddy Holly himself. When he moved to Albuquerque in 1959 he was hired by Riedlings and began selling all models of Fender guitars and other popular electric-guitar brands, such as Gibson and Gretsch, to a rapidly increasing number of impassioned Duke City rock-and-roll guitarists, too. In addition, Hankins recorded an album at Petty’s studio in 1955, called “Swing Fever” in which Norman offered his piano expertise.

“[In my] first year of college [in 1961 before I established the sound studio], I drove on weekends to Clovis to play with the 5 Counts. They even came here to play a job at the Student Union Ballroom.

”The Student Union Ballroom, or the SUB as it was called by the University of New Mexico students, was the desired venue for the early up-and-coming bands, and the first standout Ventures’ cover band in Albuquerque, the Chessman, ruled the event early on. The Knights was the second Ventures’ cover band and soon followed, and so did Red Feather recording artists, Lindy and the Lavells, an up-and-coming vocal group, who developed a strong UNM-student fan base:

“After getting married, I joined Lindy and the Lavells with Joe Martinez and Tom Ferguson to play jobs in Albuquerque. So I married my High School girlfriend after I finished [my] first year of college.”

But recording bands and licensing their tracks to record labels of note with great success that John witnessed Petty achieve, was not in the immediate cards for him. The talent of the musicians with whom John worked wasn’t the problem; he had some good ones, but perhaps the talent for getting the major labels to listen to their tracks was. John did not have a lot of success in finding that person who could get it done, so he formed Delta Records, and released a number of his artists’ tracks on 45 rpm beginning in 1964. That didn’t get it done either:

“Bob Padilla and I worked together for a while, but he got off into the world of acting and we parted ways. He helped set up the sessions we did with Larry Brummett with Buck Owens and the Buckaroos producing. We had little success. I [laid tracks on] Freddie Williams, Eugene Evans, The Saliens, Jack Kane, Thee Chekkers, The Sidewinders and Howard Stansell, [and] I had made deals with Starday in Nashville [and got some] 45's released. I finally produced an album on Heart with Bob Barron, Carl Silva, and Siegling and Larrabee.”

Wagner had great hopes with the Wickham brothers and considered them very talented “at pleasing crowds and entertaining.” But their working relationship faltered due partly to alcohol and drugs, which was common with most aspiring artists:

“Johhny Dagucon was also a big part of that magic. I believed Louie [Wickham] was an exceptional writer in the vein of Kristofferson, Willie Nelson, Roger Miller and other great artist in those times. They had a style and presentation that seemed to have great hope. I would get a lot of comments that Louie couldn't sing and that Hank was better, but I always believed it was a combination of talents that made them interesting.

“We started out with a small hit on ‘Little Bit Late.’ I signed them to management and recording agreement, and Dexter Shaffer of Starday and I worked very hard to get them to the right places. Their albums never sold nationally but Louie sold many in New Mexico. I funded the costs of what he sold, but he kept the money from the sales for himself.

“The next big moment was when Jim Stafford on the Smothers Brothers show recorded ‘Little Bit Late’ and ‘Husband in Law’ for use on the CBS show. We had a good payday on that [especially via] BMI. I let the management side go eventually because the stress and problems were way too big for the work and no income from it. I was doing it in hopes of taking them to a higher level of success. Back then it seemed common that all music movers drank, took drugs, and lived on the wild side. I thought it was part of the game of success. I learned that personalities and alcohol could create impossible situations and started guarding myself from the trauma and let downs.

“The last recording to happen for us was ‘$60 Duck,’ which I moved to MCA with some scary wheeling and dealing thinking it would be the big one! Once MCA bought it I realized they thought they bought an automatic winner, but wouldn’t stay with it if it didn't have big success on its own. I finished the ‘God Help the Working Man’ album hoping they would take it, but they lost interest.

“I released a couple of Louie's records on my own. ‘The Territorial House’ and ‘God Help the Working Man.’; the others were with Starday Records. Louie could sell lots of product, and I didn't want him to fail because of financial problems. I was lax about charging him for product to keep the relationship going, looking for bigger success. Louie had never been good at finances or business and I got a taste of how bad it was by the product I extended to him on credit. Over the years it became a huge amount on a project I spent a ton on with no return [(end of Story).

“My story of Louie is longer than we have time for. I still believe he was a unique talent and wish it had come out better for us.

“Louie and I parted ways at that time and never worked together again.”

Sidro and the Sneakers was arguably the most talented Albuquerque rock-and-roll/soul band of the time, and Wagner strongly believed that the group’s talent coupled with the strikingly beautiful voice of Beverly Brown would be the musicians to fatten his corporate account:

“When I started college in 1961 I would get haircuts at a barber shop run by Ray Garcia, Sidro's brother. I believe he told me about the music scene because he had a band, too. He introduced me to David Nunez one day in his shop. David was 17 years old. Sidro and the Sneakers were playing at a city youth club behind the Highland Theatre on Lead or Coal. I went to see them and the house was packed and really rockin'. I introduced myself and said I would like to talk them about producing records for them. I had already produced ‘Not Just Jazz,’ and it was my calling card for being a recording engineer.

“I met with Sidro and the band, and we signed a contract for [recording, publishing, and producing]. I was in the basement of the dental office, and it was a killer to get Don Rude's B3 Hammond down the narrow stairs! We cut ‘You Belong to Me,’ and it [shot] to number one on KQEO; [then we] started looking for more songs. About that time, I met Billy Sherman at Valiant records and he fed me material for them to look at. They added Bev Brown and we did some songs [provided by] Sherman. I added her to the recording contract and we moved forward. I always signed contracts on everything because I had learned the importance of that before investing time and money.

“I

had bona-fide agreements on them based on the agreements that Norman used to

sign artists. About that time they started playing Vegas and traveling,

and I [spend the majority of my time trying] to get action going on our

recordings.”

“I

had bona-fide agreements on them based on the agreements that Norman used to

sign artists. About that time they started playing Vegas and traveling,

and I [spend the majority of my time trying] to get action going on our

recordings.”But because of the long distance between him and the touring band, they began to drift apart:

“I had met Billy Sherman at Valiant records on one of my LA trips. He had big hits with the Association, [and] he was riding high with [the Cascades’] ‘Rhythm of the Rain.’ He was very nice to me and offered to always listen to my material. We never really connected on much, but he had a staff of great writers. When I played some of Sidro and Beverly's recordings for him, he gave me some song demos to have them record. We did ‘It's Just Not Funny Anymore’ and he showed it around. White Whale, who had the Turtles, liked it, signed them as a group, and dropped me like a hot potato. I learned some hard lessons in my life.”

“I worked with many talented people who I thought had the magic, realizing it was simply a game of chance and risk taking. Freddie Williams, The Chekkers, Deni Lynn and the Saliens, Freddie Chavez, David Nunez, The Sidewinders, Jackson Kane, Mayf Nutter, Mose McCormack [were some of them, and] I still believe in the things they did, but unfortunately we didn't make the big time. I eventually turned to writing music for advertising and just offering recording service, which was very successful for me.”

According to John, he ran into a lot of wannabees and flakes in the music business that were coming out of the woodwork. The great Duke City Garage Band explosion was at its peak:

“After I produced ‘Swamp Water’ for Frank Zappa's management firm, Third Story Music, one of their producers Leon Danielle said he had a deal with Motown's new label Natural Resources and wanted me to produce product for the deal. I produced Heart and Corliss Nelson for Motown and eventually had a single with Motown on ‘The Battle is Over’ by [my group, the] John Wagner Coalition. I received about $36,000 in front money and it disappeared quickly. We all got a taste but no fame.

“I have run into a thousand shysters and bull spinners but there have been some meaningful people along the way. I made a deal to have publishing companies with Paramount called Parakim and Parawag, but nothing happened with those and they eventually returned my copyrights. We did make some money by having two Lowie Wickham songs performed by Jim Stafford on the Smother Brother's TV show. I have tried a million things and spent a million dollars doing it. But I am just another guy with a dream.

“Right around 1965 or so when I was running my studio on Sierra Drive Southeast, the gentleman that started New Mex Sound [who] was named Jerry Wilson, [looked me up]. He was pretty full of himself to say the least. One day he said he would like to check out my studio, and I said okay even though I didn't like showing my studio to competition in the early days very much. He came over and looked around, made a few comments and then, as he was leaving said ‘Just wanted to see what I had so that when he put me out of business he could pick it up at a bargain.’ I remember thinking what nerve and arrogance he had and he didn't seem very impressive to me at all. But when he went out of business I bought some valuable items from him including a boom mic stand I still have that has New Mex Sound written on it. With all the great people I've met, I've [also] met a ton of phonies and scammers!

“There is a lot of dirty laundry from music connections and dreams. I tried to work with people based on their talent and not so much on their personal habits or behavior. I actually thought in the early days that being an outlaw or difficult was part of the whole musical trip. But in time, as I worked with people, I found it was their character that was important. People with good intentions and qualities didn't necessarily [make it] hard to work with because of bad habits. But when the long term character of a person became clear and it was a conflict to my goals and character, stress would rise to levels I didn't believe worth it. When I broke it off with Louie my employee and partner in music, Dexter Shaffer, asked me to not give up. I said enough was enough and it would never work out for us in the future. I have never given up on Louie's recorded performances and songwriting talents. I still believe in that magic he had. I tend to not want to publicly talk about the nasty details of my journey. I felt the same way about Tommy Bee, and there were many reasons why we could not continue a relationship with projects on my Mother Earth label. I had a lot more pleasant relationships than bad ones.

”The financial pressure became too much, and both John and his dentist brothers were feeling it. Sure, John did well with some of his projects, but they fell short of accomplishing a financial boon like Petty did. Norman’s connections with the mainstream record labels were strong in the late ‘50s, and a slew of takers for his productions and talent for hooks in both instrumentals and vocals were knocking on his door. As a result, a number of his releases rose high in the Billboard charts, beginning with one of his own instrumental accomplishments in 1954 “Mood Indigo.” Some Petty’s late ‘50s engineered instrumental hits were “Wheels” by the String-A-Longs (Norman’s best instro) and “Bull Dog” by Raton, New Mexico’s tune maker, George Tomsco and his band, the Fireballs. But his vocal-produced hits are far too numerous to mention.

A partnership breakup was imminent:

“It (sound production) started as a hobby in college and slowly grew into something much bigger. We formed a corporation John Wagner Productions, Inc. As life and marriages intervened from all sides we finally reached an impasse about the company and [in 1984] I found a way to purchase the assets and move on after about twelve years of having partners. We shared in the early Copyrights until my brother Rex passed and gave his stock to me. There were very difficult times and trials back in those days.

“I had no money and finally decided to set up a studio in my house on Marron Cr. NE. I was divorced and turned the living room into a studio and the den into a control room. My daughter and son lived with me and it was crazy times to keep things together. I recorded the last Merle Travis LP there and Sassy Jones recorded their album with John Standish producing. They would come in after getting off work at a club and work from three am till the morning hours. I also finished the ‘New Mexico Sound of Enchantment’ LP in the house studio. Eventually I remarried and decided I needed to try a commercial facility again. I made a deal in the early ‘80s to take 1300 sq feet at 12000 Candelaria NE and with the help of Auge Hays, remodeled the space and moved in. Things began to turn around then and business grew in all areas, especially automotive advertising. I then expanded a few years later to the 3700 facility in the same complex and kept the smaller one also for a short time. I entered a time period of good healthy business and success.

“

I was 24 when I moved into my house, but sold my equipment to raise cash and bought new equipment that I moved to Candelaria Street.“When I was on Sierra DR. SE [in Albuquerque], Jackson Kane came to the studio and was from the music scene in the Midland, Texas area. Over time we built a friendship and relationship to try and find success in the business. He told me on our first meeting he was a member of the Teen Kings, Roy Orbison's band in the late ‘50s. I had seen Roy many times but couldn't make the connection of him being there. Many years later I found a picture with Roy Orbison's autograph, and right there by his name was Jack Kennelly's autograph! We had great laughs about that. I had signed him to a recording contract by that time.